Required Minimum Distributions, or RMDs for short, are one of the more positive financial “problems” you can have in retirement. Simply put, you’ve invested money in tax-deferred retirement accounts, and now the government wants its slice of cake. Once you reach a certain age, the IRS requires you to withdraw a portion of these funds each year, which becomes taxable income.

While the concept seems straightforward, there’s a lot more going on behind the scenes. This article walks through what accounts are affected, when RMDs begin, how they are calculated, what happens if you don’t comply, and how inherited accounts are handled.

RMDs apply to most tax-deferred retirement accounts. These include:

- Traditional IRAs

- SEP IRAs

- SIMPLE IRAs

- Employer-sponsored plans like 401(k)s and 403(b)s

These accounts all received favorable tax treatment on contributions, meaning the money went in pre-tax and grew tax-deferred. Now that you’re older, the IRS requires a portion to be withdrawn so it can be taxed. Inherited IRAs—both traditional and Roth—also come with RMD rules, though they are slightly different and will be covered later.

It’s important to distinguish between tax-deferred and post-tax retirement accounts. Roth IRAs, Roth 401(k)s, and even rarer accounts like Roth 403(b)s are funded with after-tax dollars. Qualified withdrawals from Roth IRAs are entirely tax-free—including earnings. As such, Roth IRAs are not subject to RMDs during the original owner’s lifetime. Roth 401(k)s and Roth 403(b)s previously required RMDs, but as of 2024, they no longer do thanks to SECURE Act 2.0.

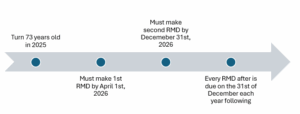

As of 2025, the magic number for a RMD is 73. You are required to take your first RMD by April 1 of the year following the year when you turn 73. After that, RMDs must be taken annually by December 31. If you delay your first RMD until the following April, you’ll still need to take a second distribution in that same year—once by April 1 and again by December 31—which could potentially increase your tax bill. Hopefully, the timeline with an example below clears up any confusion.

There is one notable exception to the RMD rule. If you are still employed and do not own more than 5% of the company, you can delay taking RMDs from your current employer’s 401(k) plan until you retire. However, this exception only applies to that employer’s plan; you’ll still need to take RMDs from other IRAs or previous employer accounts once you hit the age threshold.

RMD amounts vary from year to year and person to person. They’re calculated based on your age and account balance, using life expectancy data from IRS distribution tables. To determine your RMD, you take your total balance across applicable accounts at year-end and divide it by the distribution period for your age. For example, at age 73, the distribution period is 26.5, which keeps your withdrawal relatively modest in early years. This divisor decreases as you age—dropping into single digits by your mid-90s—resulting in larger withdrawals over time. There are different tables depending on your marital situation. The most used is the Uniform Lifetime table, but the other tables are needed for certain circumstances related to age of spouse and marital status. The table included will be the uniform lifetime table.

Distributions from tax-deferred retirement accounts are taxed as ordinary income. To help cover this, there’s a default federal withholding rate of 10%. However, you can adjust this rate—or opt out entirely—depending on your tax situation. Planning your withholding can prevent an unpleasant tax bill during filing season.

Failing to take your full RMD can result in significant penalties. The IRS imposes a 25% excise tax on the portion you failed to withdraw. For example, if your RMD is $10,000 and you only withdraw $7,000, you’ll owe a $750 excise tax on the remaining $3,000. You’ll also owe regular income tax on the full distribution once it’s eventually taken. Fortunately, the IRS provides some leniency. If you correct the mistake and take the missed RMD within two years, the excise tax may be reduced to 10%. Additionally, filing Form 5329 with a letter explaining the reasonable cause and steps taken to fix the issue may result in the IRS waiving the penalty altogether.

Inherited IRAs have special rules that differ depending on the beneficiary’s status:

- Non-eligible designated beneficiaries, such as most adult children or friends, must empty the inherited IRA within 10 years of the original owner’s death if that death occurred after 2019. This is known as the 10-year rule.

- Eligible designated beneficiaries, such as spouses, minor children, disabled or chronically ill individuals, and beneficiaries less than 10 years younger than the decedent, can use the “stretch” option, allowing them to take distributions based on their own life expectancy.

If the original account holder had already begun RMDs before their death, the beneficiary may also be required to continue annual distributions within the 10-year period. Even Roth IRAs that are inherited must follow these rules—non-spouse beneficiaries will need to empty the account within 10 years, even though distributions are still tax-free.

If you have several retirement accounts, the rules can be a little tricky:

- Traditional IRAs, SEP IRAs, and SIMPLE IRAs: You can aggregate these accounts and take your total RMD from anyone (or combination) of them.

- 401(k)s and 403(b)s: You must calculate and withdraw the RMD separately from each plan. You cannot aggregate across different employer-sponsored plans or mix them with IRAs.

RMDs are flexible when it comes to how you take them. You can take your entire RMD as a lump sum, set up monthly withdrawals, or even withdraw weekly, so long as the full annual amount is taken by December 31. Choose the method that best aligns with your budgeting and cash flow needs.

While no one likes being forced to do anything with their money, RMDs can be seen in a more positive light. After all, you’re being required to spend or reinvest money you’ve saved and watched grow over your working life. With proper planning, you can minimize penalties, manage tax impact, and even use distributions to support your goals—whether that’s travel, gifting, or charitable giving.

Distribution Period Chart based on Age

| Age | Distribution Period |

| 73 | 26.5 |

| 74 | 25.5 |

| 75 | 24.6 |

| 76 | 23.7 |

| 77 | 22.9 |

| 78 | 22.0 |

| 79 | 21.1 |

| 80 | 20.2 |

| 81 | 19.4 |

| 82 | 18.5 |

| 83 | 17.7 |

| 84 | 16.8 |

| 85 | 16.0 |

| 86 | 15.2 |

| 87 | 14.4 |

| 88 | 13.7 |

| 89 | 12.9 |

| 90 | 12.2 |

| 91 | 11.5 |

| 92 | 10.8 |

| 93 | 10.1 |

| 94 | 9.5 |

| 95 | 8.9 |

| 96 | 8.4 |

| 97 | 7.8 |

| 98 | 7.3 |

| 99 | 6.8 |

| 100 | 6.4 |

| 101 | 6.0 |

| 102 | 5.6 |

| 103 | 5.2 |

| 104 | 4.9 |

| 105 | 4.6 |

| 106 | 4.3 |

| 107 | 4.1 |

| 108 | 3.9 |

| 109 | 3.7 |

| 110 | 3.5 |

INNOVA is a SEC registered investment adviser. Information presented is for educational purposes only intended for a broad audience. INNOVA is not giving tax, legal or accounting advice, consult a professional tax or legal representative if needed. The opinions expressed herein are those of the firm and are subject to change without notice. The opinions referenced are as of the date of publication and are subject to change due to changes in the market or economic conditions and may not necessarily come to pass. Any opinions, projections, or forward-looking statements expressed herein are solely those of author, may differ from the views or opinions expressed by other areas of the firm, and are only for general informational purposes as of the date indicated. Be sure to first consult with a qualified financial adviser and/or tax professional before implementing any strategy discussed herein.