Our brains evolved in a world where the risk of a lion attack or starving to death far outweighed potential portfolio losses. It’s no wonder that these amazing bio-computers sitting between our ears are ill equipped right out of the box to deal with the decisions we ask them to make regarding our investments. Classic finance is based on theories like the Efficient Market Hypothesis which assumes all actors are rational. But a more modern approach called Behavioral Finance is based on the fact that you, me, and the rest of us are not rational. We’re normal! Read on to take a look at five errors that our well-meaning but irrational brains cause us to make.

Availability Bias

Because our brains developed over millions of years in an environment where we were forced to make snap decisions to get us out of trouble, we rely heavily on mental shortcuts that will lead us to a sufficient answer even if it may not be the optimal answer. We developed to quickly recall if a berry was edible or not, not necessarily to decide if a berry was the most nutritious option available to us. We continue to think like this today as evidenced by the availability heuristic or availability bias. We treat information that is easily recalled as more important than information that is less readily available. We typically only use information that we just heard to decide whether or not to purchase or sell a stock. Because of this, we end up investing in things that are repeated constantly in the news. By behaving like this, we are giving up the chance to invest in something that may be a much better investment.

Anchoring

The price we should pay for an engagement ring is somehow burned into our collective memories. Two months’ salary has been the standard for years. Where did this number come from? Tough to say exactly but my guess is that it was someone who sold engagement rings! Regardless of who came up with that benchmark, it’s stuck in our minds and many of us gauge the value of the engagement ring we purchase based on whatever two months of our salary ends up being. A rational person would realize that the price of the ring is no indication of our love for our fiancé, but we do it anyway because we aren’t rational, we’re normal. This is an example of anchoring which is an irrational way to gauge the validity of a purchase or sale. Many times, we set our anchor as the first price that we see. For example, if we just started investing today and saw Amazon (Ticker:AMZN) at $2,145 a share and then watched it fall to $1,500, our brains may automatically decide that $1,500 is a great deal. We make this assumption solely based on the share price’s move relative to our anchor and not on the underlying fundamentals of Amazon’s business.

Mental Accounting

Question 1: You’re at a mall and you’re looking at cell phones. You find one you like and it’s $1,000. Your friend calls you and says he found the same phone at another mall 15 miles away that’s $750. Do you get in your car and go to the other mall to buy that phone instead?

Question 2: You’re at a dealership looking at cars. You find one you like that you like and it’s $49,000. Your friend says he can get you a deal at another dealership 15 miles away for the same car for $48,750. Do you get in your car and go to the other dealership to buy that car instead?

Depending on their aversion to getting into a car and driving 15 miles, a rational person would either say “yes” to both or “no” to both. However, many people answering these questions would travel to the other mall for the cheaper cell phone but not to the other dealership for the cheaper car. Based on the size of the purchase, they have assigned a different value to the $250 they would save by driving 15 miles. Maybe you’re saying to yourself, “I knew where you were going with that the whole time. I’d do the rational thing!”. Ok, well try this one on for size, let’s say you have an investment account of $20,000 and a separate account for your kid’s college funds also with $20,000. How would you feel about losing $10,000 in your kid’s college fund? Any different than if it was $10,000 of your own investment account? If it would feel different to you, it’s because of the mental accounting that you’ve done. Because you assigned a use for the money, you’re viewing one dollar as different than another dollar. While it’s normal to feel that way, it isn’t rational!

Disposition Effect

The theories that we’ve discussed so far are based on the works of Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky and their findings in their 1979 work, Prospect theory. Their findings also brought to light the disposition effect in which they observed that investors hate losing WAY more than they like winning. This has led to a peculiar behavior that investors engage in where, to avoid a loss, they’ll hold on to a losing stock much longer than they would hold a stock that has done well. In other words, people are more likely to sell a stock after a small gain than they are to sell as stock after a small loss. This goes against the rational behavior because history has shown that the stock market has momentum and positions that have done well over the last six months typically continue to do well and vis versa for a stock that has done poorly. Realizing gains on paper makes us happy yet we want to hold off on selling because realizing losses hurts. This myopic loss aversion can be lessened by taking a longer-term view of investing. If we view an investment as a process that will span decades, we’re less susceptible to these feelings, good or bad, over a very short time period.

Bandwagon Effect

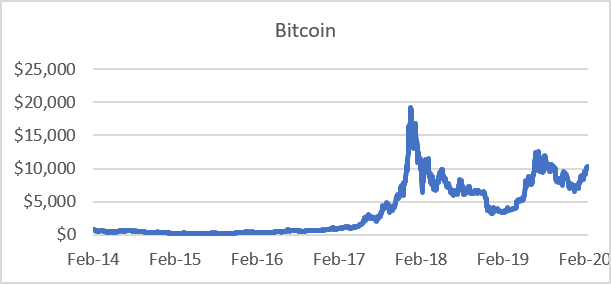

Grouping up has been beneficial since the dawn of man. Whether to take down a large animal that we’d never be able to take on alone or to join together to fight off a rival clan, being part of a group has been in our best interest. Being part of a group is so ingrained in us that we apply this same behavior to investing even when we don’t realize it. Look at bitcoin’s famous run up.

Source: Yahoo Finance

Had the fundamentals of bitcoin changed at all from February 2015 when it was worth $237 to December 2018 when it was closing in on $19,000? No, nothing had fundamentally changed with Bitcoin over that time period but it appreciated over 7900%! As news coverage picked up, more and more people jumped into the Bitcoin market causing prices to skyrocket even though nothing had changed fundamentally with the investment. We like investing in groups because we are deeply afraid of missing out on rewards that other people are getting and, interestingly, losses are actually more acceptable to us when we’re not alone in experiencing the loss. “Hey, I might be down but so is everyone else”.

Behavioral finance is a relatively new and very large topic that can fill an entire book. The important take away from this blog post is to recognize that there are times when all of us will act irrationally while investing. Keeping the topics that we’ve discussed in mind is a good start but always be aware of your real goal, whatever it may be, while you invest. By doing so, you’ll have a better chance of steering clear of these behaviors that we are all guilty of. Working with professionals like us at Innova Wealth Partners can also be a great way to be coached through situations where we may be susceptible to irrational, but normal, investment behavior.

Innova Wealth Partners, LLC (“Innova”) is a registered investment advisor. Information presented herein is for educational purposes only and does not intend to make an offer or solicitation for the sale or purchase of any specific securities, investments, or investment strategies. Investments involve risk and unless otherwise stated, are not guaranteed.

Readers of the information contained on these performance reports, should be aware that any action taken by the viewer/reader based on this information is taken at their own risk. This information does not address individual situations and should not be construed or viewed as any typed of individual or group recommendation. Be sure to first consult with a qualified financial adviser, tax professional, and/or legal counsel before implementing any securities, investments, or investment strategies discussed.

Any tax information and estate planning information contained herein is general in nature, is provided for informational purposes only, and should not be construed as legal or tax advice. Innova does not provide legal or tax advice. Innova cannot guarantee that such information is accurate, complete, or timely. Laws of a particular state or laws that may be applicable to a particular situation may have an impact on the applicability, accuracy, or completeness of such information. Federal and state laws and regulations are complex and are subject to change. Changes in such laws and regulations may have a material impact on pre- and/or after-tax investment results. Innova makes no warranties with regard to such information or results obtained by its use. Innova disclaims any liability arising out of your use of, or any tax position taken in reliance on, such information. Always consult an attorney or tax professional regarding your specific legal or tax situation.

Innova has been nominated for and has won several awards. Innova did not make any solicitation payments to any of the award sponsors in order to be nominated or to qualify for nomination of the award.